Screening in the streaming age

[Draft of article for the 2026 Film Studies conference, Melbourne]

|

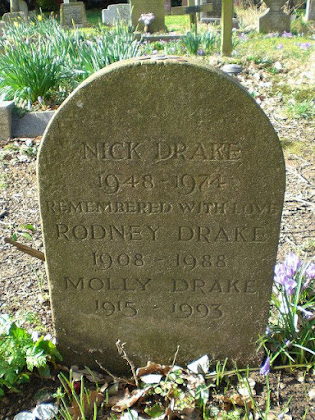

| The promise of cinema, 1896 (top) / 2026 (bottom). |

Michael Organ .......

Abstract: Film screening has come a long way from the days of the Edison Kinetoscope in the 1890s when a viewer had to manually turn a handle and look down a telescope-style tube, from silent to sound in the 1930s, black and white to colour, nitrate to celluloid, 16mm to 70mm Panavision, and from the projection era of the twentieth century on to non-physical, digital means of access such as television, optical media - video tape, laser disc, DVDs - and streaming in the new millennium, with the latter two largely removing the need to visit a cinema in order to experience film. In all instances, the technology has continued to evolve, from mechanical to digital, from physical to online. All the while, access has continued to improve ..... or has it? This is the question the current article will attempt to address, as physical media disappears, video stores disappear, local cinemas close and are replaced by centralised multiplexes, film libraries and archives face budget cutbacks and the threat of AI, and the price of access to streaming platforms and theatre tickets continues a slow creep upwards during cost of living crises. Will more actually mean less? Will it continue to be: "60+ TV channels, but nothing decent to watch!" or similiar? Will the traditional cinematic experience disappear altogether, replaced by a personalised, AI-generated product viewed on the fly?

----------------------

"Where's that Picnic video, Jack?"

Attending the cinema used to be a relatively cheap option, and in the pre-Depression era of the late 1920s Australia reached the highest per-capita attendance rate of all Western nations, such was the local popularity of film as public entertainment. This meant that for the majority of the twentieth and early twenty first centuries, young families could attend a cinema without fear of undue expense. This has changed significantly in the post-COVID-19 era, with the cost of family attendance at common multiplexes skyrocketing, and ancillaries such as popcorn and Coke breaking budgets.

As a recent (4 November 2025) Google AI overview stated in answer to the query: "What is the current cost of family cinema attendance?", the writer was informed that the average adult ticket price in 2024 was around $17.26. It was even higher for premium screens, potentially reaching $31 per adult for a V MAX movie. All of this meant that a family of four were now faced with a ticket-only cost over $100, before snacks. Of course prices vary by location, time, and screen type, but cinema-going is increasingly a luxury for higher-income families due to high ticket and concession cost.

Up until the 1970s the only way to see or experience a film for the general public was to go to the pictures, and pay to sit in a cinema and see it on a big screen. Sure, since the 1950s television had shown film on the small screen, initially in black and white and then in colour. However, cinema attendance remained the principle means of accessing film and experiencing the big screen. Eventually, by the turn of the new millennium, home theatres began to appear, with huge screens and multi-dimensional sound systems to mimic the cinematic experience. However, it was the concept of streaming - on your smart phone, laptop or home cinema - and intervening disasters such as the COVID-19 epidemic of the early 2020s, that struck the most lethal blow in regard to theatre attendance, for there was now no need to fork out a large amount of money; one simply needed to pay a monthly subscription to platforms such as Netflix, Disney+, HBO Max, Apple+, Paramount and the like.

Did not streaming promised enhanced (i.e., easier, cheaper, 24/7) assess to film? Yes, indeed, just as satellite offered increased access to television. But the saying "60+ TV channels and nothing worth watching" reflected some of the inherent problems of quantity over quality, and the fact that paying for a subscription does not necessarily ensure access to favoured or desired content . The fact is, people have specific tastes, and specific needs, and sometimes - more often than not - those needs are not filled with the provision of multiple television and online streaming channels and platforms.

Cinema attendance was relatively cheap during the twentieth century, such that a movie fan could attend a screening regularly, and then hire from a video store, or purchase a copy of the film from a major retail outlet for repeat view, alongside enjoying the "extra" included with physical media, such as extended cuts, commentaries, making of documentaries, interviews with cast and crew, and copies of associated promotional media. Ownership of, and access to, cherished items was assured, at least for the length of life of the physical media, be it video, DVD, Blu-ray, or 4K. If current trends continue, and physical media is eventually phased out, to be replaced by online streaming only, then this will mark a significant change in the ownership / access paradigm. However, many would argue that this scenario is evidence of redundancy, and the new, replacement model, is an improvement. Why? Because there is an ever increasing amount of material available online, comprising film in all its various forms and from its very beginnings in the 1890s through to the present day. This is true. But the following limitations are also true, though not always applicable across the board:

- Cost - with the major streaming platforms such as Netflix, Prime, HBO Max, Disney+ YouTube and Apple charging on average $20 Australian per month, and many families only signing up for two or three of those, the costs are significant. * Availability - many movies are available online, but the majority are at a cost, and even then they are not permanently hosted.

- Permanence -

- Quality -

- Features -

Access to access to film. And buy film. I mean, It could be a Hollywood movie, it could be a documentary. It could be a A, um, A home movie. It could be Any, any thought of moving image? It could be something on your phone. So the technology has continued to involve within all those areas. It's it's improved. Supposedly. But has it. I mean. We can now film. Watch things on our on our phone. Through streaming. We can, we can make movies. We can make videos using chat TPT and our own, our own, um, smartphone. But, Access is not all that we would expect, that would be 2025. I mean, in Australia, for example, If I want to access say the 20 best Australian films from The story, The Color game in 1906 right through to the present day. It's not that easy. If I wanted to set up a curriculum where I would, Um, that's part of the film studies thing where I have a set of say 20 Australian Films. Including documentaries, where they where they where it's relevant. It's not that easy. And I might be able to do that. For for 2 basic reasons. You know, in the first is that much of Australia's film history, haven't survived, especially films from the silent. Era and pre-World War period. Even post World War II. I mean, Captain Thunderbolt made in 1951. I, I copy didn't survive until we discovered 1 in Prague Circles of Aria. Um, just over a year ago, so Film, hasn't survived. That's 1. And That's 1 Problem. The other problem is, If it has survived, is it available? Is it accessible? And the answer is often. In many ways, no, no, even if it has been digitized and etc. Etc. So if we want to look forward, we want to look forward to tomorrow and the day after and the future. My vision would be where All the important material all the culturally significant important material. Film material. We're talking about here. You could, you could make the same argument for audio as well. Whether it's AC DC's first album, or The soundtrack to, um, That ABBA movie. Or whatever. If you want to access, my idea would be that within the next 5 years. Those 20. Significant films are freely available. For everyone every student, whether it's Someone in Primary School, Secondary School. Or tertiary education, or TA or whatever. That the, the material is available. It's in good quality Condition. It's not it's not labeled and has watermarks and all this sort of material over it. It's untouched as as soon as pristine or as as best possible condition as possible. Not edited it's it's, it's got the original Um, it it hasn't it hasn't been censored or edited in because someone in say 20, 55 says, no, we can't show this. We can't show that or someone in 2025 says, we can't show this or we can't show that And, I'm a teacher and I can go. Okay. Here's where all the films are. I can. And I can say to my students and, and I can say to them, okay, I want you this week, I want you to watch this. I want you to watch that. I want you to watch that, and I know, they can go home, and they can see it on their phone. They can see it on their streaming, television service or whatever. And so that raw material becomes the basis for My curriculum. My Film studies. Element. Now ideally, if they're doing more intense work, Not just looking at the film but also investigating aspects of it. They can then get take that further step. And maybe they can visit a, a library, or an archive, where a lot of the material Associated material posters, Scripts, um, images of on images. Um, You know, film company, archival material, about the creation and all of the of the film Etc. They could maybe a lot of that digitized. They can access that or can they they can physically visit an archive or Library. Or gallery or Museum or whatever? To actually. Interact with that material. Physically. Now, that's not a lot to ask, I think. And the reason it's not a lot to us is because For almost a century. Now, in Australia, we've been collecting Such some material. National Library of Australia and then National film and sound archive, and archives and State Library State, libraries and University libraries, or, and archives all around the place. There's been collections of film and that material For almost 100 years now. In recent years from the last 20 or 30 years, a lot of digitization has taken place. But here's the kicker. Access hasn't necessarily improved. And, The reason for that is, there's multiple reasons, a lot of it comes down to money. And copyright and copyright is a big restriction. The Copyright Act. Um, doesn't really help. I've recently found a film that was made in 1951 in Australia. And because the The daughter of the director has claimed copyright on it even though in my view, she has no right to such copyright because The only copyright holder would have been the creator of the film because you got to remember that a film is a production of many people. It's a compiler, it's it's it's a combined effort. There's a, there's the actors the writer screen writer, the director, the production company the the set designer, the, the sound recorders, all of these sorts of people. Go to making a film. Now, not all those people own copyright, they own They according to our Copyright Act, they they have the right to Be identified for what they did but the only 1 who could the copyright actor, has copyright is the production company. And that survives for, Uh, what is it? I think it's 50 years after the initial screening or, or or 51, therefore, in 19. Or 25 years or some some sort of years are 50, 607. Yeah, after the initial screening first, premiere of the material, Okay. So, therefore Eddie film after. Made after 1951 should now be thrilled accessible. This is only on the copyright regime. I mean we should be able to get access to a lot of this material outside of copyright anyway, free access But in in this instance, The daughter of the director has claimed copyright. Which means that the copyright extends from the 70 years, after the date of death of the her Father, which is 20063 Which is. 10 and 10 years or more after the film was made. This is worse than Mickey Mouse. So, all of a sudden, We don't have access to that material because of copyright misinterpretations. And of course, The other problem is, who does own copyright is, is it the production companies, a lot of the production companies they they made the material and most of material they didn't care about. They didn't preserve it because they were just interested in making the any making money making the next 1 making the next 1, like, I put A widget production house. They were necessarily interested in preservation and things like that. But then things like Star Wars and franchises come along and they're being sold for Millions, if not billions of dollars and all of the sudden content, FY. Good quality old content was became valuable. So, We've got. Access problems because of people claiming rights over the material to see when they don't know them, or the materials still has commercial value. Therefore, it's not, it's, it's not openly accessible for schools, and it's educational institutions. If it exists at all quality might be variable. Um, So we we have these and then in recent years, live with archives or some of these institutions that hold this material of the closed down or or have financial problems Etc. So there's various restrictions and these restrictions could continue into the future Because, And I that's in the side. I think the national film and sound archive as the Australia's premier Should be working with government to ensure. To ensure that this material is accessible. It's part of our cultural heritage. They can basically the government and the nfsa can step in to say, okay, We've put in place where material that's identified as culturally significant. The the the copyright restriction copyright access elements restrictions are are minimized. Um, The, the ability to have this freely available for educational purposes is is is empath emphasized. And we have a system set up where People can get access to this, cultural the significant, um, Heritage film, and sound material. Without the threats of copyright, and we've seen we've seen increasing copyright restrictions and things like YouTube. And all this weird where there's automatic, um, identification of copyright infringing material and sometimes AI is now around where The identification is wrong, there's no copyright, but I did. But it's been identified as such by an AI and all of a sudden Access to the material to everyone is restricted. The future is uncertain, and problematic.

------------------

References

1927 cinema attendance rate

Google AI answer....

---------------------

Last updated: 1 December 2025

Michael Organ, Australia

Comments

Post a Comment